The story of Bridge of Weir in the Great War

History

You came back old soldier and you didn't

and in the end it is never a battle of truth

and lies or that no mans land between.

It's sitting at the home hearth of an evening

and having no one left to tell your stories to.

Jim Carruth, 2014. Glasgow's Poet Laureate

Bridge of Weir resident.

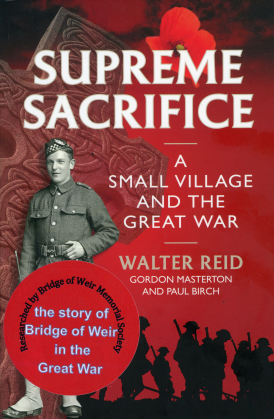

"Supreme Sacrifice: A Small Village and the Great War" by Walter Reid, Gordon Masterton and Paul Birch is a simply outstanding book that brings to life in the most immediate way imaginable the reality behind what can seem distant and oddly anonymous lists of names"... "Supreme Sacrifice" is a superbly researched book, and a very effectively organised and beautifully written one"..."The result is a book that serves as a worthy reminder of the sacrifice of the 72 men who died; and an excellent history of the war itself. It should be considered essential reading by anyone who's ever gazed at a list of names on a Scottish war memorial and wondered about the men behind the names."

Undiscovered Scotland. (Accessed 17/09/2016)

The Herald. 6 April 2017

"The men are all remembered individually, from Private William Houston, of the Royal Engineers, ... who died in 1918 after being exposed to mustard gas

... to Private John Clark, of the King's Own Scottish Borderers, a stone mason who was killed at the Battle of Loos, whose body was never recovered. At home, the book charts the "small committee of ladies who were

so desirous of raising funds" to provide a bed named the "Bridge of Weir" in the Scottish section of the British Red Cross hospital in Paris. Enough money was raised from the pulpits to buy two beds with an ambulance

- "The Lass o' Brig o' Weir" - also purchased for the Western Front. Socks, vests, gloves and pugarees - scarfs hung on the back of sun helmets - were regularly sent out.......

The Supreme Sacrifice deftly weaves the tales of war with the tales of home, with hope sadly overshadowed by reality on many occasions."

The Scotsman. 12 November 2016

This is a story of 72 young men whose names are commemorated on war memorials in a village in the West of Scotland. A village like many others in Britain with similar stories to tell. A village that was hundreds of miles away from the theatres of war, yet was severely affected. A village that would never look on the world in quite the same way again. The war was to change everything.

The unveiling and dedication of Bridge of Weir War Memorial on 26th June 1921

The idea for telling their story came from the 12 names on a memorial in Freeland Church of Scotland in the village, and a realisation that the memorial could tell us nothing about them, not even their first names. The real people behind the names were becoming forgotten.

A group of volunteers came together to try to find out more. We thought that the personal stories might remind us of the shocking impact of the war on the village. We hoped that young people might empathise with those who lost their lives close to their own ages. We all shared a view that a more faithful commemoration of those who died may lead to greater respect for their sacrifice. The project would be worthwhile for that reason alone.

And then it grew. Inspired by the early success in researching the Freeland Fallen, we extended the project to include all 69 on the village memorial. Then two more names were discovered on other church memorials. A family's researches showed that William McClure had a valid claim for inclusion, and his name was added to the village memorial in October 2014.

It seems likely that around 690,000 Scots enlisted, of whom 110,000 died - a death rate of 16%. Not all historians agree on that statistic. One well-documented sample of combatants formerly employed by the Scottish Cooperative Wholesale Society cites 2075 who enlisted of whom 315 were killed, a death rate of 15.2%. However, what we do know is that Bridge of Weir's 72 young men who were memorialised paid the ultimate price for being high-risk participants in one of the world's bloodiest conflicts. Something of their lives, times and tragically early deaths is told on this site.

But spare a thought too for those who fought and later returned to Bridge of Weir, around 380 of them if the national ratio applies. None of them would have returned unaffected by the conflict; many were wounded; most would be traumatised or burdened with memories they'd sooner forget. They were no lesser heroes than those who made the supreme sacrifice.

Some Additional Village Connections

Modern means of researching digital databases and other sources has revealed other men with an apparent connection to the village, through birth, residence or marriage, who were killed in the Great War but are not on any village memorial, for whatever reason. Perhaps they had no-one to speak for their inclusion at the time. To date, names on this list are: Frank Aikenhead; William Brown; George Campbell; William Craig; George Cummings; James Duncanson; John Eadie; J Fergus; Alexander Ferrier; William Ford; Hugh Fox; David Galbraith; Archibald Hart; John Hassan; Gilbert Blackie Kirk; John Anderson Mann; Allan Maund; Caldwell B Meiklem; Edward McAuley; Andrew McFarlane; John McNulty; Charles McPhee; William Reid; Alexander Smith; John Steel; William Ward; William Willis; Alexander Young.

Patrick Norris died of influenza complications in New Zealand in December 1918 and James Cameron died of TB in Randwick, New South Wales in March 1921. From research carried out by Cathy Craig, sapper Thomas McNaught McLellan, Royal Engineers, died aged 27 in Bellahouston Military Hospital on 12th March 1920. He had lived in Beechwood, Main Street, Bridge of Weir. In other circumstances some of these names may have been accepted for the village memorial in 1921.

Their sacrifice is not diminished through their names not being carved in stone in Bridge of Weir.

TO CITE THIS PAGE: MLA style: "Bridge of Weir Memorial". bridgeofweirmemorial.co.uk. Date of viewing. http://www.bridgeofweirmemorial.co.uk/index.html